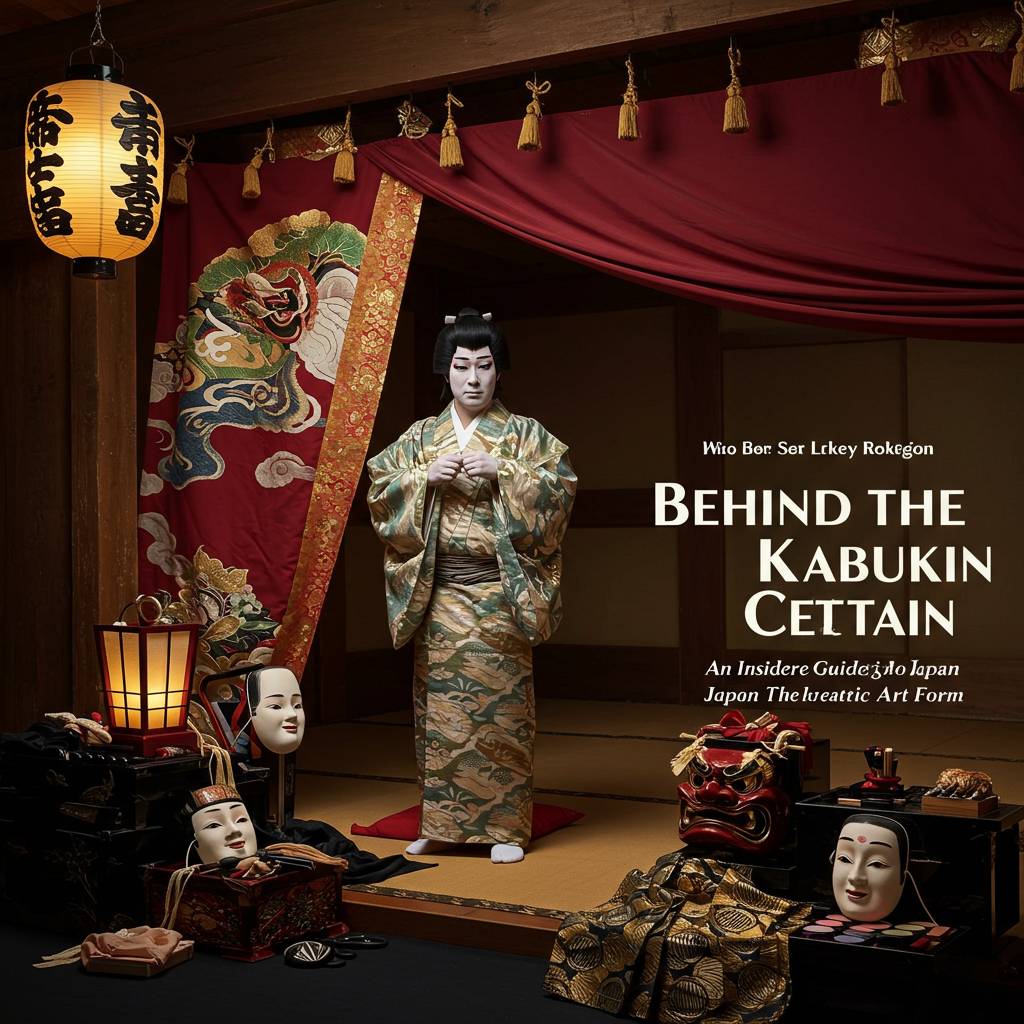

Stepping into the vibrant world of Kabuki theater is like unlocking a treasure chest of Japanese cultural heritage that has captivated audiences for centuries. As one of Japan’s most distinctive traditional art forms, Kabuki combines elaborate costumes, stylized movements, and powerful storytelling into an unforgettable theatrical experience. Whether you’re planning your first visit to a Kabuki performance or simply curious about this unique cultural phenomenon, this comprehensive guide will take you behind the ornate curtain to reveal insights that transform you from casual observer to informed enthusiast. From the closely guarded techniques of Kabuki masters to practical tips for appreciating your first performance, join me as we explore the fascinating journey of this art form from its Edo period origins to its current status as a UNESCO-recognized cultural treasure. Discover the secrets, traditions, and evolution of Kabuki that have made it an enduring symbol of Japanese artistic expression for over 400 years.

1. 5 Hidden Secrets of Kabuki Masters that Few Foreigners Ever Discover

Kabuki theater represents one of Japan’s most mesmerizing cultural treasures, yet beneath its elaborate costumes and dramatic face paint lie secrets that even dedicated foreign enthusiasts rarely glimpse. These hidden elements define true mastery in this centuries-old theatrical tradition.

First among these secrets is “mie,” the dramatic frozen poses that punctuate performances. While tourists might recognize these striking moments, few understand that master actors spend decades perfecting microscopic muscle control. Every finger position, eye movement, and body angle follows traditions passed down through generations. True masters can hold these physically demanding poses with such stillness that veteran audience members watch for the subtle trembling that indicates supreme effort and control.

Second, kabuki’s vocal techniques extend far beyond the distinctive chanting style. Masters develop a specialized breathing method called “fukikomi” that allows for sustained vocal projection without modern amplification. This technique requires years of training to master the ability to project whispers to the theater’s furthest corners while maintaining character integrity. Foreign observers rarely recognize when this technique is being employed, yet Japanese connoisseurs can identify specific actors solely by their breathing patterns.

The third secret involves “keshō,” the iconic makeup application. While tourists admire the striking results, few realize that kabuki masters mix their own pigments using closely guarded family recipes dating back centuries. The white base paint, traditionally made with lead (now replaced with safer alternatives), requires precision application in multiple thin layers rather than a single thick coat. Masters can complete their elaborate makeup in under an hour, a process that takes apprentices several painstaking hours to learn.

Fourth, veteran kabuki actors develop what’s called “yūgen-no-me” or “eyes of subtle mystery.” This refers to the ability to convey complex emotions through almost imperceptible eye movements while maintaining the painted expression. Masters train using traditional mirrors and mental visualization techniques to control minute facial muscles that communicate emotional nuance across vast theater spaces.

Finally, the most closely guarded secret involves “kata” – the hereditary movement patterns passed exclusively from master to apprentice. Unlike other Japanese arts where kata might be publicly documented, kabuki’s most powerful movement sequences remain unrecorded, transmitted only through direct mentorship. Some kata are specific to certain family lineages, meaning they can only be seen when performed by actors from those families. When these rare movements appear, knowledgeable audience members experience a connection to performances from centuries past.

These hidden dimensions of kabuki mastery explain why dedicated Japanese audience members return repeatedly to observe the same plays, discovering new layers of meaning with each viewing. For those willing to look beyond the surface spectacle, kabuki reveals itself as not merely theatrical entertainment but a living museum of artistic techniques preserved through unbroken human transmission across generations.

2. How to Appreciate Kabuki Like a Local: Essential Knowledge for Your First Performance

Attending your first Kabuki performance can be both exhilarating and overwhelming. This traditional Japanese theatrical art form, with its centuries of history and complex conventions, rewards those who come prepared. To help you appreciate Kabuki like a local, here’s essential knowledge for your inaugural experience.

First, understanding the structure helps immensely. Kabuki performances typically consist of multiple acts or plays within a single program. Traditional full programs could last all day, though modern performances are usually 3-4 hours with intermissions. Don’t feel obligated to stay for the entire production—locals often attend specifically to see favorite scenes or actors.

When you arrive at renowned theaters like Kabukiza in Tokyo or Minamiza in Kyoto, consider renting the English audio guide. This invaluable tool provides real-time translation and explains key cultural references that might otherwise be lost. For a more authentic experience, observe when the Japanese audience reacts; their “kakegoe” (shouts of approval at particularly impressive moments) signal the highlights of technical mastery.

The visual language of Kabuki is rich with symbolism. The dramatic makeup (kumadori) uses colors with specific meanings: red represents righteousness or passion, blue denotes villainy or supernatural elements, while black marks nobility. The exaggerated poses (mie) actors strike during emotional peaks are meant to be admired—these are perfect moments to join locals in appreciation.

Understanding character archetypes enhances your experience tremendously. The aragoto (rough style) characters with their bombastic movements and speech contrast with the wagoto (soft style) portraying more realistic, nuanced roles. Female characters are traditionally played by male actors called onnagata, whose stylized movements represent the ideal of feminine beauty rather than realistic portrayal.

For maximum enjoyment, arrive early to browse the theater’s program—even if you can’t read Japanese, the illustrations offer valuable context. During intermissions, observe how Japanese audience members discuss performances and actors’ techniques. Many bring opera glasses to appreciate the detailed expressions and costumes—consider bringing your own or renting them at the theater.

The music and sounds of Kabuki create another layer of meaning. The shamisen (three-stringed instrument) often drives the narrative, while wooden clappers (tsuke) punctuate dramatic moments. Listen for how these sounds coordinate with actors’ movements—this rhythmic harmony is considered one of Kabuki’s greatest artistic achievements.

Lastly, embrace the theatrical nature of Kabuki rather than expecting naturalistic drama. Its stylized expressions, elaborate costumes, and dramatic plots are meant to transport you to another world. The art form celebrates the spectacular and the emotional, prioritizing beauty and impact over realism. By approaching Kabuki with this mindset, you’ll connect with the same elements that have captivated Japanese audiences for centuries.

3. The Evolution of Kabuki: From Edo Period Entertainment to UNESCO Cultural Heritage

Kabuki theater stands as one of Japan’s most enduring cultural treasures, with a fascinating evolution spanning centuries. Beginning in the early Edo period, kabuki emerged as a popular entertainment form accessible to commoners—a stark contrast to the aristocratic noh theater. Originally performed by women, the government soon banned female performers due to moral concerns, giving rise to the tradition of male actors (onnagata) playing female roles that continues today.

The art form flourished despite repeated government restrictions, evolving from relatively crude entertainment into a sophisticated theatrical tradition. During the Genroku era, legendary playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon elevated kabuki with compelling narratives that still captivate audiences. The Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za, and Morita-za emerged as the three major kabuki theaters in Edo (modern Tokyo), establishing traditions that would define the art form.

Throughout the Meiji Restoration, kabuki faced existential challenges as Japan rapidly modernized. Many feared traditional arts would disappear amid Western influence. However, visionary performers like Ichikawa Danjūrō IX recognized the need for kabuki to adapt while preserving its essence. This period saw the formalization of kabuki as a classical art rather than contemporary entertainment.

The 20th century brought further transformation as kabuki incorporated modern theatrical elements while maintaining its distinctive conventions. The Shōchiku Company assumed management of major kabuki theaters, providing institutional stability that helped the art form survive world wars and changing entertainment landscapes. Celebrated actors like Nakamura Utaemon VI and Onoe Baikō VII became living national treasures, recognized for their mastery and contributions to kabuki preservation.

The ultimate recognition came when UNESCO designated kabuki as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, acknowledging its global significance. Today, institutions like the Kabukiza Theatre in Ginza and the National Theatre of Japan present regular performances, while innovative directors explore new interpretations that speak to contemporary audiences.

Despite its historical journey, kabuki remains remarkably true to its origins. The distinctive makeup (kumadori), elaborate costumes, stylized movements, and musical accompaniments continue to define performances. Modern technology has enhanced productions without compromising traditional elements—sophisticated revolving stages (mawari-butai) now operate with precision engineering while maintaining their original function.

This remarkable evolution from Edo period entertainment to internationally recognized cultural heritage demonstrates kabuki’s resilience and adaptability. By honoring tradition while embracing necessary change, kabuki has secured its place not only in Japanese cultural identity but in the global theatrical landscape.